When someone tells you they have been sexually assaulted, how do they need you to respond?

When someone tells you they have been sexually assaulted, how do they need you to respond?

Opinion Piece by Catherine Poulton, UNICEF Gender-Based Violence in Emergencies Specialist for 2gether 4 SRHR

One in three women worldwide have experienced physical and/or sexual violence at least once, leading me to ask, not if, but when someone confides about a sexual assault, do we all understand best practice in how to respond?

My work is primarily in preventing and responding to violence that women and girls face in emergency settings including sexual violence, but many lessons are universal. When training refugee camp managers, police and humanitarian responders, I refer to the ‘GBV Pocket Guide’. Whether you’re a specialist or not, it tells you the steps you should follow with one main principle at the heart of all actions: Do no harm. This means: Don’t judge, don’t doubt, don’t give advice. Instead, know your local support services including local women’s associations, health centres and others. This is about preparation. Everyone should download the GBV Pocket Guide, because at some point, we will all need it.

In humanitarian contexts, 70 per cent of women experience gender-based violence (GBV) compared with the 35 per cent worldwide. This horrifying reality is why my job exists. I was recently deployed to Burundi to train response teams on how to prevent and deal with sexual violence, an initiative funded by 2gether 4 SRHR. Earlier this year, more than 70,000 refugees fled from neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), a sharp spike following decades of ongoing armed conflict. Burundi’s Musenyi refugee site currently hosts 17,000 although it was initially built to accommodate 10,000. Many women and girls have survived sexual violence perpetrated by armed groups and armed forces in DRC, when fleeing to Burundi, and incidents have also been reported in the refugee site.

The rate of sexual violence has never been higher in DRC, with UNICEF estimating that a child in Eastern DRC was being raped every half an hour. This is a systemic crisis including children as young as toddlers. In many conflict settings, rape has been used as a weapon of war and a deliberate tactic of terror.

UNICEF works with partners[1] to improve the safety of women and girls. To do so, interventions such as safety audits in sites like Musenyi are regularly conducted. During these exercises, refugee residents are asked to circle dangerous areas in red on a map. This ‘community mapping’ allows refugees to provide feedback and solutions, without having to describe their personal story of rape, reducing shame, stigma and re-trauma.

Burundi is ranked 187th out of 192 countries on the 2025 Human Development Index, hosting refugees from one of the world’s most conflict-affected countries with an emergency response plan woefully underfunded. Despite the dedication of Burundian authorities, UN and other partners, I witnessed toilets without locks; sleeping arrangements mixing men with boys and health clinics lacking post-rape kits - issues identified as high risk. The Burundian authorities, UN agencies and other partners have since addressed many of these programmatic gaps, despite great challenges stemming from global funding cuts, which are preventing humanitarian responders from providing holistic care. But this isn’t the only issue.

The reality is, women’s and girls’ safety is often not considered as ‘life-saving’, and in a context of restricted resources, other interventions are often prioritised. Why don’t girls dare leave their tents, even if they need to find food or water? Because they are at risk of being raped. This is not difficult to correct, with adequate resources. Build toilets with locks, that are well lit and demarcated; engage with communities to identify risks and interventions; and equip health services to deliver lifesaving services for survivors. These measures are efficient, cost effective, and avoid public health emergencies - all whilst keeping women and girls safe.

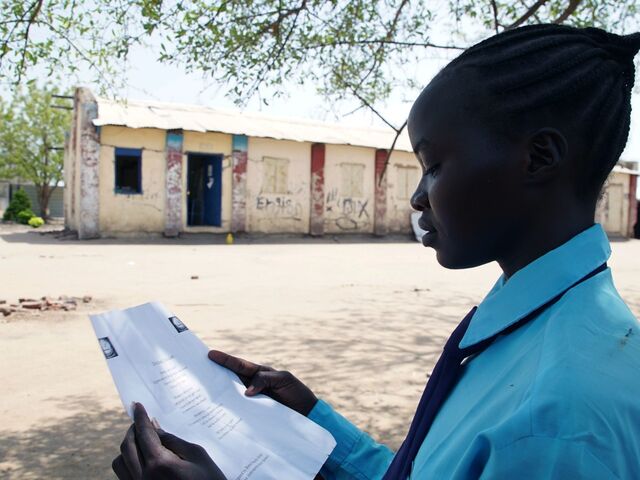

Safety audits are standard for the GBV sector, and UNICEF recommends this approach be taken by all humanitarian responders, whether providing food, water, sanitation or education. Thanks to donors like Sweden, in South Sudan and Somalia, through the 2gether4 SRHR programme, safety audits have now been integrated into most humanitarian response plans, helping to ensure women and girls have access to safer facilities.

This approach of preparedness is a lesson that we should all consider in our daily lives. Without doubt, someone you know has or will experience violence in their lifetime. If they confide in you, what do they need from you? Wherever you are in the world, if someone has experienced sexual violence, it’s important they visit a health clinic equipped with post-rape kits. These kits are crucial in the first 72 hours after a sexual attack, including pregnancy tests and PEP (Post-Exposure Prophylaxis) medication to prevent HIV transmission. Specialist follow-up support and counselling for survivors of sexual violence is also required to help rebuild lives. Until the safety of women and girls becomes a priority everywhere, I keep my GBV pocket guide handy.

Catherine Poulton is UNICEF’s GBV in Emergencies Specialist for 2gether 4 SRHR, a joint UN Regional Programme, in partnership with Sweden, which brings together the combined efforts of UNAIDS, UNFPA, UNICEF and WHO to improve the sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) of all people in Eastern and Southern Africa. For a one stop shop of information and resources in Africa, visit theSRHR Knowledge Hub.

[1] UNICEF, UNHCR, UNFPA, WFP, and the NGOs Save the Children, International Rescue Committee, Social Action for Development and Terre des hommes- Lausanne;