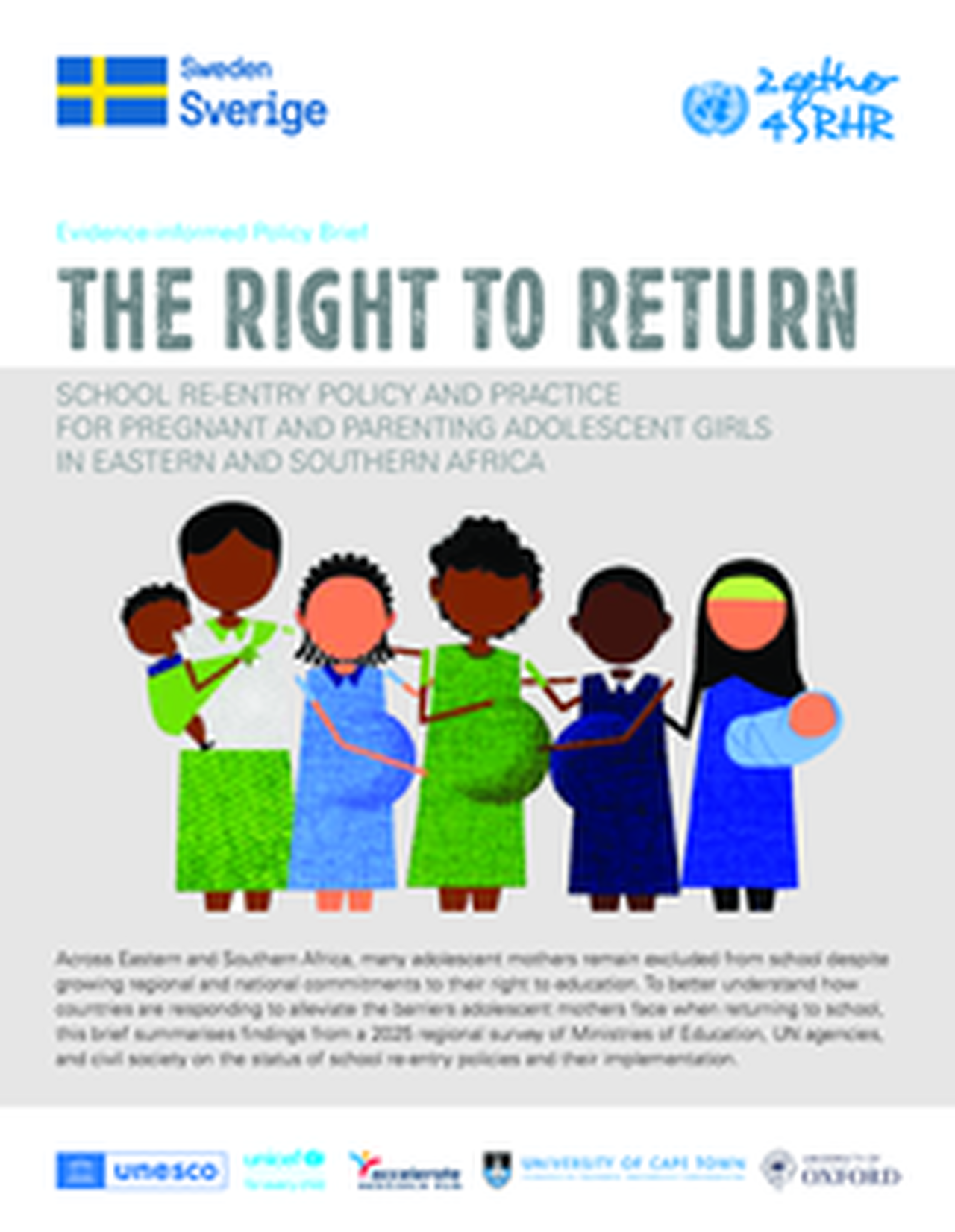

The Right to Return: School re-entry policy and practice for pregnant and parenting girls in Eastern and Southern Africa

Right to Return Policy Brief

2 MB

Across Eastern and Southern Africa, many pregnant and parenting adolescents remain excluded from school despite growing commitments to their right to education. The Right to Return summarises findings from a 2025 regional review across 21 countries on the status and implementation of school re-entry policies. The brief highlights gaps between policy and practice, examines barriers such as stigma, resourcing and limited guidance, and identifies actions to strengthen education systems so that adolescent mothers can return to, remain in, and complete their education.

Go to external page: Download